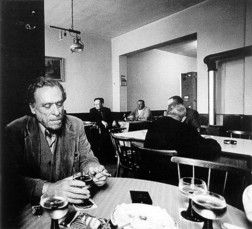

The Ghost of Charles Bukowski, a novel excerpt or a partial tribute

At the end of my freshman year in college, a professor loaned by Love Is a Dog From Hell by Charles Bukowski. The 300+ page book of poetry about horseracing, prostitutes, drunkenness, despair and the rare moment of transcendence makes a strange source for an epiphany, I warrant. But as a 19-year-old who had been carrying a poetry journal for the two years or so prior, that book offered one brilliant illumination and made me forever indebted to the misanthrope poet of Los Angeles. Bukowski just wrote. He didn't wait for a subject; he didn't edit himself or circumscribe his thoughts; he didn't sweat line breaks or unpleasant odors. He wrote what he wanted. That's what Dog from Hell said to me: write what you want.

Ever since then, I've thought about my relationship to Bukowski's work, and have dabbled with imaginings about his ghost. I include one of these poems in "Monster Poems." Recently, I also uncovered a novel concept and first few chapters with the working (or not working) title "Better Safe Than Haunted by the Ghost of Charles Bukowski." Needs work, I reckon. But here's the first chapter for your reading enjoyment.

If you'd like to read more, click that "Follow" link up at the top of this page. If I get a few of you to do so, I'll post chapter two.

Ever since then, I've thought about my relationship to Bukowski's work, and have dabbled with imaginings about his ghost. I include one of these poems in "Monster Poems." Recently, I also uncovered a novel concept and first few chapters with the working (or not working) title "Better Safe Than Haunted by the Ghost of Charles Bukowski." Needs work, I reckon. But here's the first chapter for your reading enjoyment.

If you'd like to read more, click that "Follow" link up at the top of this page. If I get a few of you to do so, I'll post chapter two.

Chapter 1

“Misery is the privilege that finds you when you need it

to,” quips Charles, belting me across the face. My chin whips over my left

shoulder, and I go down. Needless to say, nobody sees the blow that fells me.

Conveniently for Charles, he’s non-corporeal. Annie gasps in surprise. My

toppling is a far cry from the expected response to the question, "Do you take this woman to love, cherish, honor, obey, in sickness and in health, 'til death, yadda yadda…"

From

my vantage point at carpet level I can see already where this is going, this

ceremony, this afternoon, this evening, tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. I

can see it going a long way away.

“Here’s

your mantle,” says Charles. “Wear it proudly.”

I

lift my face up to the shoes of my Uncle Joe and Aunt Maddie who have come in

from Cleveland. Cries of confusion and concern arise from all quarters. I

postpone saying anything to anybody until it’s Annie, my dad and the pastor who

are closest.

“I

can’t,” I say. They know what I mean. I see Annie’s dad has the message, too, but

there’s this clinging we people do, denying what’s patently true because we

want some explanation that will change the truth. I notice that Annie

understands: her eyes are brimming. The pastor’s eyes are rolling, like he’s

heard it all before and now he’s going to have to advocate for the rest of his

fee. It’s my dad that’s desperate for words.

“What

do you mean? You can’t what? What’s going on? Do you know who’s here?”

“Come

on, dad,” I say, cold as Charles, who is now nowhere to be seen. “You get it.

I’m not going through with this. I’m sorry. This whole scene isn’t for me. That’s the bitter

truth.”

Dad’s

hand comes down like a spanking on my shoulder, though his grimace looks as if

he means to brace me for the customary conclusion to this event—the one that includes a hailstorm of uncooked rice. I shake him off, and on the tide of

murmurs, understanding and disparagement, I ride out of the chapel at a speed

walk. Outdoors on the steps isn’t nearly far enough, so I keep walking fast,

down the lawn to the sidewalk, down the sidewalk, past the fence, across a

street…

Like

a lost penguin, I walk quick, turning corners, seeking some way to home in on

where I’m supposed to go. I keep turning so the people who will soon be leaving

the church will not chance to drive past me. I don’t want the people who knew

me to find me. I don’t want the people who thought they’d know me to tell me

anything, either. I walk for at least an hour in the blasting Miami summer

until I’m soaked through and God knows where.

Charles

appears for a moment to draw my attention to a shadowed doorway. “In here,” he

rasps.

It’s

dim and rancid with a single black bar and a half-dozen wounded naugahide

stools. A couple tables and mismatched chairs mill around like anonymous

alcoholics. A booth forebodes against the far wall. A vintage but worthless

jukebox appears to be unplugged. A beer-brand lampshade stubbornly asserts,

“Miller.”

The

craggiest, most Caucasian man I’ve seen in Florida eyes me.

“Miller,”

I say.

“What’s

with the tux?”

“Walked

out on my bride to be.”

“Truth,”

Charles enunciates. “More beautiful than a bride. Better than peanuts with

beer.”

“Shut

the fuck up.”

The

bartender looks ready to swing a haymaker at me.

“Not

you,” I say. “The voices in my head.”

“Okay,”

says Charles. “But this one just came to me. Then I leave you to your mug of

cold piss:

heart

broke

and

breaking

sometimes

the whole

mass

of the world

stops

a minute

to

nod

its

distaste

for

you.

you’re

tired,

so

it rolls off

like

beer foam.

in

a minute

your

turn is over,

and

the next

man

in line

throws

the

meaningless

dice.

As I pound the beer, Charles swirls away into the stale effluvia of this place, and I move on to whiskey.

Comments

Post a Comment